La question de l'immigration reste très débattue, entretenue par une pression migratoire forte aux frontières de l'Europe. En 2004, la France comptait près de 5 millions d'immigrés en métropole, soit 8,1 % de la population. Plusieurs textes de loi sont intervenus sur ce thème.

Les images de naufragés sur les côtes européennes et de frêles esquifs interceptés au large des Canaries, de Lampedusa ou de Malte émeuvent toute l’Europe. Les reportages montrant des centaines de candidats clandestins à l’immigration autour de Ceuta et Melilla ou du tunnel sous la Manche marquent les esprits.

Les termes du débat sur l’immigration se sont renouvelés. En amont des questions liées à l’intégration, on s’interroge notamment sur la possibilité d’adapter les flux migratoires aux besoins de main-d’œuvre ou sur les moyens de lutter contre l’immigration clandestine notamment outre-mer.

Dans son ouvrage "L’immigration" (collection Débat Public, 2006), Laetitia Van Eeckhout présente et explique le thème de l’immigration en 135 questions, en précisant les conditions historiques, les évolutions et les enjeux de ce phénomène.

Les deux questions reproduites ici définissent clairement les notions essentielles des débats sur l’immigration : immigré, assimilation, intégration, insertion.

Qu’est-ce qu’un immigré ?

« Est immigrée toute personne née de parents étrangers à l’étranger et qui réside sur le territoire français. Certains immigrés deviennent français par acquisition de la nationalité française, les autres restent étrangers : "Tout immigré n’est pas nécessairement étranger, et réciproquement", souligne l’Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE). La qualité d’immigré est permanente : un individu continue à appartenir à la population immigrée même s’il devient français par acquisition. En revanche, on parle souvent d’immigrés de la deuxième ou troisième génération pour désigner les enfants dont les parents ou les grands-parents sont immigrés. Pour ceux, nombreux, qui sont nés en France, c’est un abus de langage. Les enfants d’immigrés peuvent cependant être étrangers, s’ils choisissent de garder la nationalité d’origine de leurs parents. »

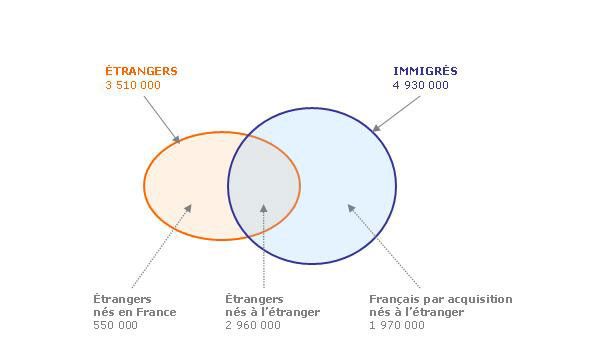

Etrangers et immigrés en France

Les données issues des enquêtes de recensement de l’INSEE permettent de bien distinguer étrangers et immigrés en France.

Assimilation, intégration ou insertion ?

« Ces trois termes ne sont pas neutres et reposent sur des philosophies politiques (très) différentes. L’assimilation se définit comme la pleine adhésion par les immigrés aux normes de la société d’accueil, l’expression de leur identité et leurs spécificités socioculturelles d’origine étant cantonnée à la seule sphère privée. Dans le processus d’assimilation, l’obtention de la nationalité, conçue comme un engagement "sans retour", revêt une importance capitale.

L’intégration exprime davantage une dynamique d’échange, dans laquelle chacun accepte de se constituer partie d’un tout où l’adhésion aux règles de fonctionnement et aux valeurs de la société d’accueil, et le respect de ce qui fait l’unité et l’intégrité de la communauté n’interdisent pas le maintien des différences.

Le processus d’insertion est le moins marqué. Tout en étant reconnu comme partie intégrante de la société d’accueil, l’étranger garde son identité d’origine, ses spécificités culturelles sont reconnues, celles-ci n’étant pas considérées comme un obstacle à son intégration dès lors qu’il respecte les règles et les valeurs de la société d’accueil. »

Pascal Salin aborde un sujet délicat pour les libéraux : le concept de nation. À cette occasion, il pose les questions de l'intégration culturelle et des discriminations, et par là celles du racisme et de l'immigration.

Clik here to view.

L'IMMIGRATION DANS UNE SOCIÉTÉ LIBRE

discrimination raciale,racisme,raciste,L'émigration et l'immigration devraient être totalement libres car on ne peut pas parler de liberté individuelle si la liberté de se déplacer n'existe pa...

Hommage aux immigrés clandestins

par Gérard Bramoullé, professeur d'économie à l'Université d'Aix Marseille III (source [1])

L'immigré clandestin pèse moins que l'immigré régulier sur les comptes de la Sécurité Sociale, et il n'alimente pas les arguments de ceux qui fondent leur xénophobie sur le prélèvement qu'opèrent les étrangers sur les moyens et les services du "Club" France, tout simplement parce qu'il ne dispose pas des papiers nécessaires pour accéder à la plupart des faveurs de l'État-Providence.

Face aux problèmes de société que soulève l'immigration et malgré leurs divergences idéologiques, les hommes de l'État - ceux qui sont en place, comme ceux qui voudraient l'être - sont au moins unanimes sur un point : il faut lutter contre l'immigration clandestine. Cette lutte constitue la priorité affichée de toutes les politiques d'immigration qui nous sont proposées, de quelque parti qu'elles émanent. Une unanimité trop criante pour être honnête... En fait, bouc émissaire facile d'un problème difficile, l'immigré clandestin présente des avantages que n'a pas l'immigré régulier.

En premier lieu, pour son travail au noir, l'immigré clandestin abaisse les coûts monétaires et non monétaires de la main d'oeuvre. II renforce la compétitivité de l'appareil de production et freine le processus de délocalisation des entreprises qui trouvent sur place ce qu'elles sont incitées à chercher à l'extérieur. Il facilite les adaptations de l'emploi aux variations conjoncturelles et augmente la souplesse du processus productif. Le clandestin, qu'il soit étranger ou national, ne fait qu'anticiper les allègements légaux de charges sociales qui tendent à se généraliser. Animant le réseau de "l'économie informelle ", il participe à ce qui est à la fois une régulation non négligeable des fluctuations économiques, et une bouée de sauvetage pour nombre d'institutions en situation désespérée.

L'immigré clandestin qui ne participe pas au financement du système de protectorat social, ne participe pas non plus à son exploitation au détriment des cotisants, du fait même de sa clandestinité. Ceci compense cela, tout simplement parce qu'il ne dispose pas des papiers nécessaires pour accéder à la plupart des faveurs de l'Etat-Providence, dont on connaît les exigences en matière de paperasserie. L'immigré clandestin pèse ainsi moins que l'immigré régulier sur les comptes de la Sécurité Sociale, et il n'alimente pas les arguments de ceux qui fondent leur xénophobie sur le prélèvement qu'opèrent les étrangers sur les moyens et les services du " Club" France.

Enfin, ceux qui craignent de voir un jour le droit de vote accordé aux étrangers résidant régulièrement sur le territoire national peuvent être rassurés avec l'immigré clandestin qui, par définition et à cause de son irrégularité, ne pourra participer à ces réjouissances électorales. La politique, qui n'est souvent qu'un moyen de faire prévaloir la subjectivité de sa foi en la parant de l'autorité de la loi, est une voie dont l'accès lui est fermé. Ce n'est pas l'immigré clandestin qui pourra utiliser le monopole public du pouvoir de coercition pour nous imposer des règles de vie contraires à nos habitudes.

Mais justement, l'immigré clandestin ne viole-t-il pas ces règles de vie en société ? Pas nécessairement, car s'il est vrai qu'il ne respecte pas les règles définies par l'État, il est faux de croire que ces règles étatiques recouvrent toutes les règles de la vie en société. La législation n'est pas le Droit, comme la légalité n'est pas la légitimité, et comme aucune loi ne fixe les principes de la politesse. Dès lors que l'immigré clandestin respecte les règles naturelles de la vie en société, telle que par exemple le respect de la parole donnée, et même s'il est hors-la-loi, il mérite moins l'expulsion que ceux qui font l'inverse. Enfin, dans un monde où la puissance tutélaire de l'État se fait de plus en plus étouffante, ce clandestin inconnu nous montre le chemin de l'indépendance et réveille notre sens anesthésié dé la liberté individuelle. A ce titre, il valait bien cet hommage qui n'a du paradoxe que la forme.

Pour le libre échange et une immigration limitée

article tiré du "Symposium sur l'immigration" publié par The Journal of Libertarian Studies , volume 13 (2), été 1998; par Hans-Hermann Hoppe traduit par Hervé de Quengo [Le numéro du "Journa...

Immigration: What is the Liberal Stand?

Anthony de Jasay

Liberals abhor frontiers and feel that people should be no less free to move than goods. Yet as the pressure of the poor to move to richer lands is mounting and illegal immigration is proving politically difficult to curb, the liberal ideal must be re-assessed.

The reduction of relative poverty—what sociologists call relative deprivation—looks far more difficult if not impossible. Demography will see to it that real income per head in the poor world will increase only a little faster than in the rich world where indigenous population will be stagnant or falling. At the same time television and its ilk will keep undermining social stability and will see to it that people in the poorer regions of the world should see their own standard of life more and more by the yardsticks of how the other half lives. They now seem to feel more miserable even as their physical circumstances become less appallingly bad.

The upshot is that the pressure to immigrate to the fairylands of Western Europe, the U.S. and the white ex-British dominions is rising and is destined to go on rising perhaps for several decades. Economists may be tempted to say that free trade will serve as a safety valve, for where goods and capital move freely, people need not move to make themselves better off. But as the depressing story of the Doha Round shows, trade is not getting free enough fast enough, and capital movements will never be broad and sweeping enough as long as Bolivian, Russian or Zimbabwean governments can lay their hands on it in the hallowed names of national sovereignty or social justice.

Immigration, of course, is nothing new. During the great migrations after the fall of Rome, entire peoples moved from Asia to Europe, though this was not a movement into settled countries across defined frontiers. From the 8th century onwards there was a broad stream of involuntary migration from Central and East Africa, with Arab traders catching or buying from tribal chiefs black Africans to be sold into slavery. Estimates of black African slaves moved to the Middle East over the thousand years to the 17th century vary from a low of 8 million to a high of 17 million. (It is claimed that the great majority of male slaves were castrated, which would explain why there is next to no black minority population in Arab lands). After the 17th century, demand for slaves from the Caribbean, Brazil and the southern United States priced the Middle East out of the market and the slave trade passed into white hands. Until the abolition of slave trading (though not of slave owning) in 1806, 8 to 10 million more black Africans were shipped across the Atlantic.

There have since been two radical changes. Immigration ceased to be involuntary. People moved from Europe to North America and other lands with temperate climates of their own free will, attracted by economic incentives. Entry to these lands was unrestricted. The second great change, coming roughly with World War II, was when the entrance gates started to close. Immigrants were no longer admitted as a matter of course, but as a selective privilege granted sparsely. More and more immigrants turned into intruders, slipping in through porous frontiers and living and working with no legal status.

There are now an estimated 8 to 12 million illegal immigrants, mostly Hispanics, in the U.S. Europe's illegal immigrants are ethnically far more mixed, coming as they do from black Africa and the Caribbean, Arab North Africa, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Ceylon, Indonesia, Turkey and the Balkans. An estimated 570,000 live in the United Kingdom. French guesses range between 200,000 and 400,000, though the reality is almost certainly higher. The annual influx into both countries may be about 80,000.

The economic effect of illegal immigration is on balance probably positive, though it is controversial in countries with high unemployment such as Germany, France and Italy. It can hardly be disputed, though, that without illegal immigration from Mexico, the U.S. would not have had its spectacular growth of recent years, and the notion that illegal immigrants steal the jobs of whites in Europe comes from voodoo economics. Illegal immigration hurts, not economically, but because it is resented as a loss of control by a society of whom it will admit into its midst—a loss that is easily accepted when the coloured immigrant population is yet small, but becomes fearsome when the cumulative weight of decades of uncontrolled illegal entry starts to change the ethnic and cultural profile of a country. The Netherlands is arguably the most tolerant country in Europe, but with 1,700,000 non-white inhabitants, it has recently become violently nervous about the future and slammed on immigration controls that are draconian by Dutch standards.

The European Union is budgeting to give 18 billion euros over seven years to help African economic development (a flagrant example of hope prevailing over experience for the umpteenth time), on the understanding that African governments will do their share in reducing the flow of illegal migrants. Many other initiatives are being taken to strengthen frontier controls, to restrict the legalisation of illegals and to deport some to their countries of origin as a deterrent to would-be illegals. None of these attempts seems to have much of an effect seriously to reduce the influx of unwelcome immigrants. Only quite radical measures might stem the tide, for whose severity current European opinion has, understandably enough, no stomach.

Classical liberals have a bad conscience about immigration controls, let alone severe ones. The liberal mind has always disliked frontiers and regards the free movement of people, no less than those of goods, as an obvious imperative of liberty. At the same time, it also considers private property as inviolable, immune to both the demands of the 'public interest' (as expressed in the idea of the 'eminent domain') and of the rival claims of 'human rights' (satisfied by redistributing income to the poor who have these rights). Private property naturally also implies privacy and exclusivity of the home.

One strand of libertarian doctrine holds that it is precisely private property that should serve as the sole control mechanism of immigration. Immigrants should be entirely free to cross the frontier—indeed, there should be no frontier. Once in the country, they should be free to move around and settle in it as if it were no man's land, as long as they do not trespass on any part of it that is someone's land, someone's house, someone's property of any sort. They can establish themselves and find a living by contracting to work for wages and to find a roof by paying rent. In all material aspects of life, they could find what they need by agreements with owners and also by turning themselves into owners. Owners, in turn, would not object to seeing immigrants get what they had contracted for.

A very different stand can, however, be defended on no less pure liberal grounds. For it is quite consistent with the dictates of liberty and the concept of property they imply, that the country is not a no man's land at all, but the extension of a home. Privacy and the right to exclude strangers from it is only a little less obviously an attribute of it than it is of one's house. Its infrastructure, its amenities, its public order have been built up by generations of its inhabitants. These things have value that belongs to their builders and the builders' heirs, and the latter are arguably at liberty to share or not to share them with immigrants who, in their countries of origin, do not have as good infrastructure, amenities and public order. Those who claim that in the name of liberty they must let any and all would-be immigrants take a share are, then, not liberals but socialists professing share-and-share alike egalitarianism on an international scale.

*Anthony de Jasay is an Anglo-Hungarian economist living in France. He is the author, a.o., of The State (Oxford, 1985), Social Contract, Free Ride (Oxford 1989) and Against Politics (London,1997). His latest book, Justice and Its Surroundings, was published by Liberty Fund in the summer of 2002.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.